Economics is the study of resource allocation under certain constraints. It is a field that has existed since time immemorial and has undergone a metamorphosis as the world developed.

Every science evolves, and Economics is no exception. This article summarizes the history of economics and revisits the various schools of economic thought that shaped modern economics.

Economics is the science that analyzes the pattern in which societies produce goods and services and consume them. Economic theories have had a lasting impression on global finance throughout history and have emerged as integral in our lives.

Today, the government of every country, top international agencies, and large financial institutions have their bench of economists who help them formulate policies. However, there is a drastic change in the assumptions behind each economic thought.

The phase of modern economic growth started in the mid 18th century in Britain, and by the end of the 19th century, it gradually spread to other parts of the world. The countries closer to England, the epicenter of the Industrial Revolution, were faster to see the changes and eradicate extreme poverty.

Likewise, the countries near ports saw a pick up in international trade while those with a conducive climate witnessed a boom in agriculture. These are some of the factors that fuelled modern economic growth and became subjects of analysis for various economists and philosophers across time. A particular school of economic thought has influenced each phase of economic growth and the theories generated subsequently.

This article takes a brief look at the history of economic thought.

Economics In Ancient Times

Economics has always existed in historical times in some form or the other. Evidence found in ancient Greece, China, and India suggests that the political leaders in that era believed in economic policies.

In ancient Greece, Economics was seen more as household management. Hesiod was an ancient Greek poet whose earliest work was the fundamental origins of economic thought.1 In his poem, Works and Days, the first 383 verses of the 828 verses highlighted the problem of scarcity of resources in contrast to the magnitude of man’s desires and goals.

In 493 BC, Fan Li, a Chinese businessman, politician, and strategist, also acted as an adviser to King Goujian of Yue on economic issues.2 Li developed ‘golden’ rules for business operations and discussed seasonal effects on markets and business strategy. Li also formulated the strategy of ‘taking ten years to produce and accumulate, and another ten years to nurture’ for King Goujian’s kingdom.

The Arthashastra, written by Chanakya, philosopher and Prime Minister of the Maurya Empire in Ancient India, somewhere between 322 and185 BC, was one of the earliest books on economics.3 Interpreted as the Science of Money, Arthashastra was a treatise on history, economics, commerce, politics, and management, among other subjects.

1485: Economic Ideas By St. Thomas Aquinas

In 1485, St. Thomas Aquinas, a ‘scholastic philosopher’ from Italy, published ‘Summa Theologica’, an authoritative book on medieval economic thought. Aquinas was a disciple of Albert, the Great, and a professor of theology and philosophy.

His economic ideas revolved around religious and moral issues and included private property, just price, and usury. The economic theories of Aquinas reflected the ideals of the Bible, Canonists, and Aristotle.33

16th to 18th Century: The Age Of Mercantilism

In the 16th to 18th centuries, most of the European nations adopted mercantilist ideals of various magnitudes. Mercantilism was an economic practice in which governments capitalized on their economies to enhance state power by victimizing the economies of other countries.4 Governments went to any extent to ensure a positive balance of trade and accumulate wealth, mostly in bullion form.

Precious metals like gold and silver were a critical factor in Mercantilism. They were considered the fundamentals of a nation’s wealth, and if a country had no access to mines to produce them, they had to be obtained by trade. Mercantilism also advocated that Colonial possessions should serve as export markets and as suppliers of raw materials to the host country. We can say that mercantilism laid the foundation for the early development of capitalism by emphasizing the profit motive.

Later, mercantilism received severe criticism because of its stringent premises. Its influence began to fade off towards the late 18th-century with the development of classical economics in Britain and physiocrats in France.

1750 to 1840: First Industrial Revolution

The first Industrial Revolution happened between 1750 to 1840 and was mostly confined to Britain. Employment opportunities and wages increased across various sectors, especially manufacturing. It also boosted urban housing demand leading to significant changes in the city layout, planning, and infrastructure.5

A higher level of education and the requirement for advanced technologies led to newer inventions. The industrial revolution boosted Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and the development of the modern capitalist economy. It also marked the beginning of stable GDP growth for the next century.

After the British became aware of their advancements, they restricted exporting machinery, manufacturing techniques, and skilled workers. However, the British monopoly did not last long, especially after they sensed lucrative industrial opportunities overseas. At the same time, European business people wanted to leverage British know-how in their local industries.

William and John Cockerill built machine shops at Liège and introduced the Industrial Revolution to Belgium in 1807. Thus, Belgium became the first country in Europe to see an economic transformation. Gradually other countries followed, and the ones that leveraged industrialization became self-sufficient and less reliant on imports.6

1765 Onwards: Classical Economics

Classical economics, also known as the school of classical political economy, originated in Britain’s late 18th and early 19th centuries. However, French and Spanish scholars and philosophers also made significant contributions to this school of thought.7 Classical economics focused on economic growth and economic freedom.

It promoted the idea of laissez-faire or the power of thoughts and beliefs to take their course in free competition. The theories of classical economics also offered a detailed explanation of the concept of value, price, supply, demand, and distribution.

The classical economic theory advocated the transition of countries from monarch rule to a capitalist democracy with self-regulation.

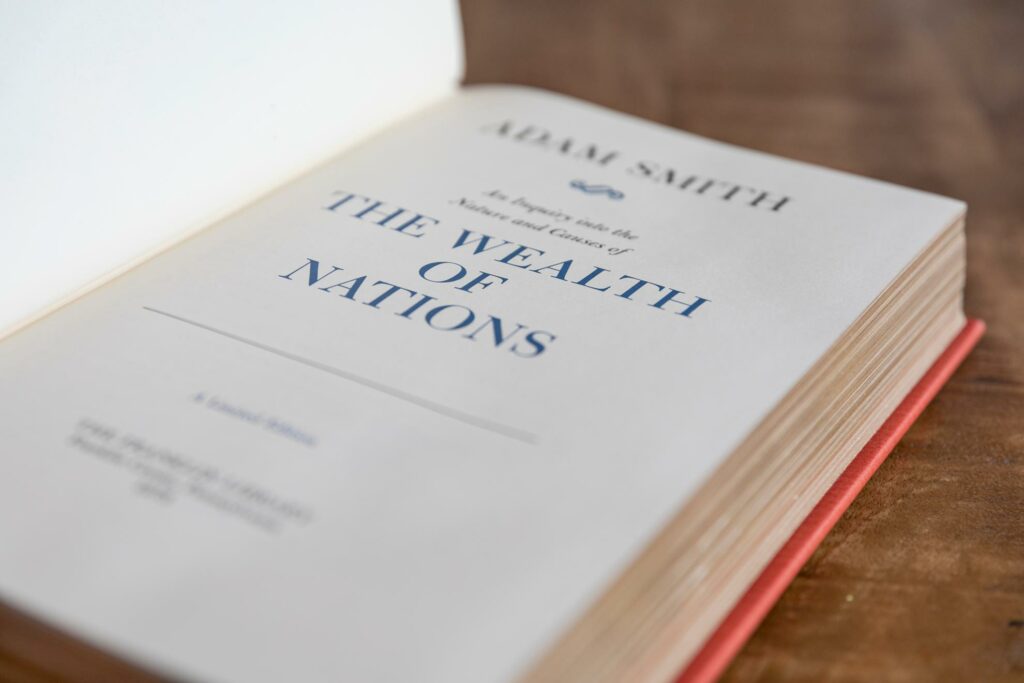

1776: Adam Smith’s Wealth of the Nation

Adam Smith was a Scottish philosopher who authored the path-breaking book, “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations”—also known as “The Wealth of Nations” in 1776, the year in which the American Declaration of Independence was also signed. 8

Adam is also regarded as the Father of Modern Economics. Through this book, Smith described that the industrialized capitalist system would end the mercantilist system, which held that wealth was fixed and finite. Mercantilism believed that hoarding gold and overseas tariff products were the only means to get wealthier.

Adam Smith believed that economic development depended on the foundation of saving, labor division, and broader market reach. Through the concept of ‘Laissez-Faire’, Smith propagated that the state should avoid imposing any restriction on an individual’s freedom to make choices.

In his first publication in 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith said, “How selfish soever man may be supposed, and there are some principles in his nature which interest him in the fortune of others and render their happiness necessary to him though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.”9

1798: Malthusian Theory

Thomas Malthus was a British philosopher and economist who developed the Malthusian growth model, or an exponential formula for projecting population growth. His philosophy on population growth was outlined in his book “An Essay on the Principle of Population” published in 1798.10

Malthus’s theory explained that populations would continue to expand until growth is halted or reversed by external causes like war, calamity, disease, or famine. His exponential formula explained that the population would double in 25 years but the food supply would grow in an arithmetic progression. The theory also stated that the food supply would expand at a slower rate than the population because of which there will be a food shortage in a few years.

1803: Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste Say was a classical French liberal political economist. Say’s Law of Market, propounded in 1803, stated that production is the source of demand.11 According to this law, the nation’s ability to purchase something depends on its ability to produce something and thereby generate income.

Say’s Law of Markets suggests that markets will be in equilibrium when there is a demand for something if it is supplied at the right price. Say’s law is one of the principal doctrines that has supported laissez-faire which advocates that a capitalist economy will gravitate toward full employment and prosperity with no intervention from the government.

1817: David Ricardo’s Rent Theory

David Ricardo was a classical English economist famous for his theory on rents in 1817. Also, in 1815, he published his subsequent major work in economics, Essay on the Influence of a Low Price of Corn on the Profits of Stock, and discovered the law of diminishing marginal returns applied to labor and capital.12

In his rent theory, Ricardo stated that rent is a portion of the earth’s produce paid to the landlord owing to the soil’s original and indestructible powers. Rent is a surplus that the super marginal land enjoys over the marginal land due to the law of diminishing returns.

One of the most significant assumptions of Ricardo’s rent theory is that land is a gift of nature, therefore, has zero supply price and cost of production. Ricardo also believed that landlords had a tendency to waste their wealth on luxuries instead of investing.

1848: John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill was an influential British philosopher, economist, and politician who advocated classical economic theory.13

Mill believed in utilitarianism—which stated that actions leading to people’s happiness are right and those leading to suffering are wrong.

Mill was best-known for his 1848 work, Principles of Political Economy, in which he elaborated on the ideas of David Ricardo and Adam Smith. He developed the concepts of economies of scale, opportunity cost, and comparative advantage in trade.

Mill advocated that economics should blend theory and philosophy, which should play a role in politics and shaping public policy.

Late 1800: Neoclassical Economics

Neoclassical economics is focused on the idea of supply and demand as the primary driving force behind the pricing, production, and consumption of goods and services. It emerged around the late 1800 to compete with the earlier theories of classical economics.14 Neoclassical economists argued that the consumer’s perception of a product’s value is the critical determinant of its price. They defined economic surplus as the difference between the actual production costs and retail price.

Neoclassical economics, alongside the concept of perfect competition, works as a yardstick to judge the efficiency of fundamental markets. Real markets are the ones that are neither perfectly efficient nor perfectly competitive markets.

1862-1874: Marginalisim by Jevans, Walras, & Menger

The period between 1862 to 1874 was known as a period of marginalism and credit for its development goes to Jevans, Walras, and Menger.15 The principle of Marginalism believes that economic decisions are made and economic behavior happens in terms of incremental units, and not categorically.

Marginalism answers the question about how much, excess or less, of production, consumption, buying, or selling would a person or business will engage in.

William Stanley Jevons’s book A General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy published in 1862, marked the beginning of using mathematical methods in economics. It looked at economics as a science as it was concerned with quantities. According to Jevon, economics is a mathematical discipline.

Besides Jevon, Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre (Principles of Economics by Carl Menger in 1871, and Éléments d’économie politique pure by Léon Walras in 1874 are the works that laid the founding notions of marginalist economics. 15 Carl Menger was also the Austrian school of economic thought founder, which believed in free markets and spoke against socialism and government interference in money matters.

The marginal revolution marked the beginning of a new period in the history of economic thought. Marginalism rejected the theory of labor value and favored the subjective theory of use value, ’marginal’ reasoning, and using marginal substitution rates as a concept to explain price formation.

1890: Principles of Economics by Alfred Marshall

Alfred Marshall was the dominant figure in world economics from about 1890. He specialized in microeconomics or the study of individual markets and industries instead of the whole economy or macroeconomics.

In his most popular book, Principles of Economics, Marshall discussed a slew of new concepts, such as demand elasticity, consumer surplus, and quasi rent.16 All of these played a major role in the subsequent development of economics. In this book, Marshall emphasized that supply and demand act like “blades of the scissors” and play a great role in determining the price and output of goods. Alfred Marshall’s microeconomic theories have created a great impact on the modern economic thought process.

1867: Marxism by Karl Marx

Marxian economics, or Marxist economics, a doctrine founded by Karl Marx, focuses on labor in economic development and criticizes the classical approach to wages and productivity that Adam Smith propagated.18

Marxism delves into the struggle between social classes, especially the bourgeoisie (capitalists) and the proletariat (workers). The Marxist analysis also validates the theory that economic relationships are the foundation of political and societal institutions. Marxism advocates that the economic relations in a capitalist economy would ultimately lead to communism.

Karl Marx Marxism argued that a specialized labor force combined with a growing population puts downward wages pressure. He also added that the value placed on goods and services does not represent the actual labor cost.

Marx highlighted the unorganized nature of the free market and surplus labor as the two major flaws in capitalism leading to exploitation. Eventually, he predicted that more people would resort to worker status due to capitalism, creating a revolution wherein production would be transferred to the state.

After Marx, the legacy was carried forward by Friedrich Engels during the mid-19th century.

1893: Pareto Efficiency by Vilfredo Pareto

Named after the Italian economist and political scientist Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923), Pareto efficiency is a foundation of welfare economics.17 The concept of Pareto-optimality assumes that given a choice in resource allocation, anyone would go for a cheaper, reliable, and more efficient option that is cheaper, and more efficient that improves one’s condition.

Though Pareto efficiency implies that resources are allocated in the most economically efficient manner, there may not be a fair approach. An economy is said to be in a Pareto or optimum state when no economic changes can make one option better without making at least the other worse.

18th – 20th Century: Emergence Of Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economics combines elements of economics and psychology to understand how and why people behave the way they do in the real world. It differs from neoclassical economics, which assumes that most people have well-defined preferences and make well-informed, self-interested decisions based on those preferences.

Behavioral economics came into prominence in the 1980s, but it dates back to 18th-century Scottish economist Adam Smith. As a concept, Economic psychology gained momentum in the 20th century with the prominent contribution of Gabriel Tarde, George Katona, and Laszlo Garai.19

The field of behavioral economics studies and describes economic decision-making. According to its theories, actual human behavior is less rational, stable, and selfish than traditional normative theory suggests.

1870-1914: Second Industrial Revolution

The “new” or Second Industrial Revolution happened between 1870 and 1914. The modern industry began to use many natural and synthetic resources such as lighter metals, rare earth, and new alloys, which were not utilized earlier. Coupled with these, developments in tools, machines, and computers led to automation in factories.20

From a historical perspective, this was also a period that changed political theories. Instead of the laissez-faire ideas dominating the economic thought of the classical Industrial Revolution, global institutions moved into the social and economic realm to cater to the needs of more complex industrial societies.

The world witnessed exceptional but unstable economic growth, including economic issues like severe depressions in 1873 and 1897. There was an intense battle of control between businesses and corporations. This led to the failure of several smaller companies whereas others were bought up by bigger corporations that dominated the marketplace.

The Second Industrial Revolution proved to be highly profitable for those who could capitalize on these technological advancements. This revolution also brought in the Gilded Age, a phase of great extremes in the world economy. On one hand, there was immense wealth, new opportunities, a greater degree of standardization and expansion, while on the other hand, there was extreme poverty and inequality in wealth distribution

1914: Institutional Economics

Institutional economics, also known as institutionalism, gained momentum in the United States after 1914. This school of thought viewed the development of economic institutions as an integral part of cultural development.

Institutionalism was never a significant school of economic thought. Still, its influence can be seen in the works of economists attempting to explain economic problems by incorporating social and cultural phenomena. Many consider Institutionalism helpful in analyzing the issues plaguing developing countries, wherein industrial progress directly greatly depends on the modernization of social institutions.21

Thorstein Veblen, an American economist, and social scientist founded institutional economics and was critical of traditional economics that was static.22 He attempted to establish that people are affected by changing policies and institutions, changing the perception that they make economic decisions.

1920-1930: Chicago School of Economic Thought

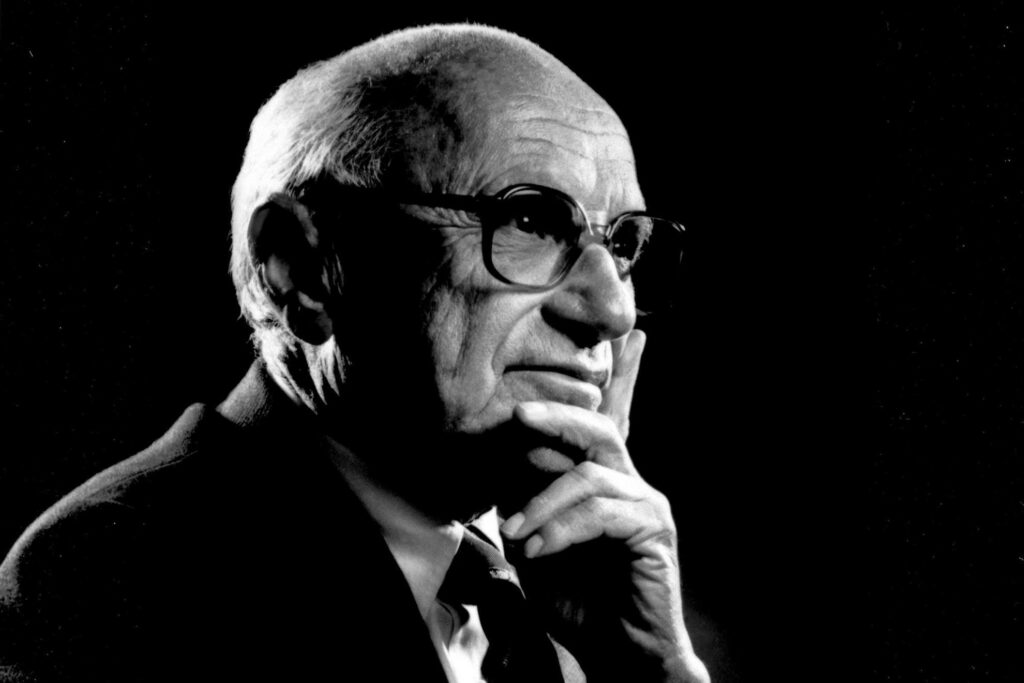

The Chicago school of economics is also a form of the neoclassical school of economic thought used in the faculty’s work at the University of Chicago between 1920 and 1930. Founded by Frank Hyneman Knight, the Chicago School of economic thought believed that free markets allocate resources in an economy the best way and that minimal or no government intervention is ideal for economic prosperity. The Chicago School projects monetarist beliefs about the economy and advocates that the money supply must be at par with the demand for money.

Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman was the most prominent alumnus of The Chicago School whose theories were utterly different from Keynesian economics. Friedman’s quantity theory of money believes that the amount of money in circulation influences the general price levels in the economy. By managing general price levels, economic growth can be better controlled in a world where individuals and groups rationally make economic allocation decisions.23

At the core of the Chicago school’s approach is its belief in the value of free markets or laissez-faire. Chicago economists have also intellectually influenced other fields such as public choice theory and law and economics, bringing about path-breaking changes in the study of political science and law.

1936: Keynesian Economics

During the 1930s, Keynesian economics developed by the British economist, John Maynard Keynes came to the forefront. Keynesian economics is a macroeconomic economic theory that studies total economic spending and its impact on output, employment, and inflation.24

Keynes described his revolutionary premise in “The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.” Published in February 1936. Keynesian economics says that to boost growth, the government should increase demand which is the primary driving force in an economy.

The theory supports the expansionary fiscal policy whose primary tools are government spending on infrastructure, unemployment benefits, and education. Keynes advocated deficit spending during the contractionary phase of the business cycle. One of the biggest drawbacks of overdoing Keynesian policies is the rise in inflation.

The Keynesian multiplier shows the amount of demand that each dollar of government spending generates. The tenets of Keynesian theory became a dominant force in the Western world. President Franklin D. Roosevelt used Keynesian economics to design his famous New Deal program. In his first 100 days in office, he used this program to increase the FDR debt by $3 billion to create 15 new agencies and laws.25

Post-1945: Mathematics Dominates Economics

The two decades after World War II can be seen as an era in which the history of economics underwent a massive transformation.

Firstly, mathematics came to dominate almost every branch of the field. The economists moved from differential and integral calculus to matrix algebra, using it to add a quantitative element to the equilibrium model of the economy. Matrix algebra is also critical in introducing the input-output analysis, an empirical method of managing several simultaneous equations.26

Secondly, post-war economics closely witnessed the development of linear programming and activity analysis that allowed the application of numerical solutions to industry-based problems. This also introduced economists to the concept of inequalities. Gradually, the emergence of growth economics extensively used difference and differential equations.

Alongside the widespread application of mathematics, a new field called “econometrics,” which combined economic theory, mathematical model building, and statistical testing of economic predictions, emerged. The development of econometrics had a substantial impact on economics as it allowed empirical testing to the ones formulating new theories.

1950: Developmental Economics

This is a branch of economics focused on enhancing fiscal, economic, and social conditions in developing countries. One of its earliest models was the linear-stages-of-growth model formulated in the 1960s by W. W. Rostow in The Stages of Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto, following the work of Marx. Development economics also examines a combination of macroeconomic and microeconomic factors determining developing economies’ structure and their domestic and international growth.27

1961: Rational Expectations Theory

The Rational Expectations theory was first proposed by John F. Muth in his seminal paper, “Rational Expectations and the Theory of Price Movements,” published in 1961 in the journal Econometrica. Muth used the term to describe all the economic situations wherein the outcome partially depends on people’s anticipation.28

One of the central assumptions of the theory states that forecasts are unbiased and that people use all the accessible information for decision-making. The other assumptions also indicate that people understand the working of economic ideas and government policies.

Using rational expectations in economic theory is not entirely new. Earlier economists like A. C. Pigou, John Maynard Keynes, and John R. Hicks determined that people’s expectations play a critical role in deciding business cycles.

After John Muth introduced the concept, other economists like Robert Lucas and T. Sargent popularized it in the 1970s and widely used it in microeconomics during the neoclassical phase.29

1969: The Third Industrial Revolution

The late 1969 and early 1970 witnessed the Third Industrial Revolution, during which everyone saw the emergence of an untapped source of energy called Nuclear energy. Besides, the third revolution is known for the rise of electronics, telecommunications, and computers. It also opened the doors to biotechnology, research, space expeditions, and other new technologies.30

Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) and Robots were two significant inventions in the industrial space that announced an era of high-level automation. The Third Industrial Revolution shifted the power from centralized global companies to diversified small and medium-sized enterprises.

This revolution brought in a quick decline in transaction costs leading to the democratization of information, energy, manufacturing, marketing, and logistics. It also ushered in a new era of distributed capitalism that changed the working of commercial life to a great extent.

1978: Emergence Of New Keynesian Theory

New Keynesian economics is a school of modern economic thought that builds upon classical Keynesian economics. The neo-Keynesian theory focuses on economic growth and stability instead of total employment. Like the Keynesian theory, it does not see the market as being self-regulating.

In 1978 when After Keynesian Economics was published, new classical economists Robert Lucas and Thomas Sargent highlighted that the stagflation of the 1970s could not be explained through traditional Keynesian models.31

Like the New Classical theory, New Keynesian macroeconomic analysis assumes households and firms have rational expectations. However, the most significant difference between the two schools differs in that the New Keynesian principle accounts for various market failures.

One of the New Keynesian school of economic thought’s central tenets is that prices and wages are “sticky,” which implies they adjust rather slowly to short-term economic fluctuations. This explains a few economic factors, such as the impact of federal monetary policies and involuntary unemployment.

2008-2010: The Resurgence Of Keynesian Policies After The Subprime Crisis

The subprime crisis of 2008 was one of the biggest economic crises in history. It led to a global recession and prompted many economists to question the existing theories. As a response, there was renewed interest in Keynesian policies, and some of the economists advocating this move were Dominique Strauss-Kahn, Paul Krugman, and Olivier Blanchard. At the same time, academicians like Alberto Alesina and Silvia Ardagna favored fiscal austerity policies for economic recovery. Tax increases and spending cuts are two of the main elements of such austerity measures.34

The Bottom Line

The history of economics shows how resources were valued and traded across periods. Despite being a dismal science, economics has always had a profound impact on society for ages, and it has become more relevant with increased globalization.

Economics has evolved over a period. In economics, theories were developed when there was a lot of physical labor and human power around. Nowadays, the economy has changed so much that the basic assumptions made by the leading economists are less relevant. Also, essential accounting tools used in early economics have grown into complex financial models, with blended mathematics for more accurate calculations.

In the paper, The Evolution of Economics: Where We Are and How We Got Here, Peter J. Boettke, Peter T. Leeson, and Daniel J. Smith stated that though Economic principles haven’t changed in the last decade, economists’ applications of these principles have.32

Firstly, the subject is now focused on “big questions” in the political economy and is willing to look beyond economics in search of answers. Secondly, contemporary economics is more empirically focused. Thirdly, modern economics has been dramatically influenced by “Freakonomics,” or the application of economic principles to offbeat topics.

Boettke, Leeson, and Smith further predict that this transformation in economics will be associated with natural language-based analysis, allowing a greater understanding of various topics to achieve social cooperation and progress.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34