A hedge fund is a limited partnership of investors that can make extensive use of more sophisticated trading, portfolio construction, and risk management techniques to improve performance, such as short selling, leverage, and derivatives, in hopes of realizing substantial capital gains.

You’ve likely heard about hedge funds in some capacity, whether interviews with successful hedge fund managers, allegations of insider trading in the news or even the portrayal of fictional hedge fund Axe Capital on Showtime’s TV drama, Billions. But what are hedge funds exactly? How do they differ from other types of funds? How long have they been around?

In this post, we’ll answer all these questions and many more to help you understand hedge funds and the critical role they play in finance and investing.

Defining Hedge Funds

We’ll start our deep dive into hedge funds with the basics – defining them.

According to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), “hedge funds pool money from investors and invest in securities or other investments to get positive returns.”

Based on this definition, a hedge fund may sound like any other pooled investment vehicle, such as a mutual fund or ETF. The definition also provides very little clarification on the kind of investments in a hedge fund. All we get is “securities or other types of investments,” which could be anything. It’s not an accident that the SEC provides such as broad definition. One of the defining characteristics of a hedge fund is how much more flexibility it has than other investment options.

What do we mean by this?

Compared to other types of funds, hedge funds have considerably more leeway in a few different respects, most notably in the investment options they can choose from and how they can charge fees. While these may sound like relatively minor differences, they have far-reaching implications, including who can invest, the level of risk, and potential returns. To see how hedge funds typically take advantage of each and how that makes them different from other types of funds, we’ll compare the typical hedge fund to the average mutual fund.

Khan Academy also does a great job introducing hedge funds and how they differ from mutual funds.

Hedge Funds vs. Mutual Funds

According to the SEC, “a mutual fund is a company that pools money from many investors and invests the money in securities such as stocks, bonds, and short-term debt. The combined holdings of the mutual fund are known as its portfolio. Investors buy shares in mutual funds. Each share represents an investor’s part ownership in the fund and the income it generates.”

On paper, a mutual fund sounds similar to a hedge fund, but the real-world differences make them drastically different investment options. These differences primarily come down to how both entities are regulated.

In short, mutual funds are heavily regulated, while hedge funds are not. This allows hedge funds to include investments or use strategies that come with considerably more risk. This additional risk comes with the potential for higher returns, but it also comes with a higher chance of capital loss. Due to the riskier nature of hedge funds, not everyone is allowed to invest in them. Only those the SEC deems sufficiently sophisticated and able to handle the higher level of risk may invest directly in hedge funds. We’ll talk about exactly who fits these criteria later in this post, but in short, the average individual typically cannot invest in a hedge fund but can invest in a mutual fund.

The final feature of a typical hedge fund that makes it different from other types of funds is compensation. One of the most appealing aspects of funds, such as mutual funds and ETFs, is their low fees. This is not the case for hedge funds.

Hedge funds typically have a unique compensation structure, leading to considerably higher fees. Part of this fee is generally based on the inclusion of performance fees, often on top of management fees. This unique structure has many implications for investors and potentially how the fund is managed, which we’ll cover later in this post.

In short, hedge funds are less regulated than mutual funds and deemed riskier, and fewer people can invest in hedge funds.

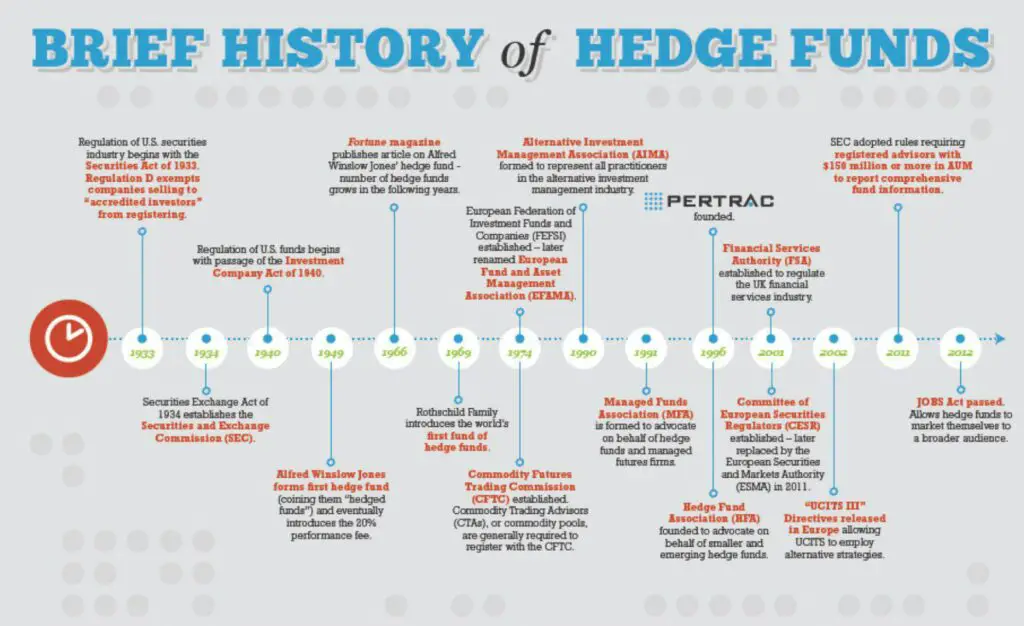

The History of Hedge Funds

Now that we know the basics of hedge funds, let’s take a moment to review their history, which can help provide us with more context about the hedge fund industry and how it grew to its present size.

Alternatively, for a comprehensive understanding, read The History of Hedge Funds.

Alfred Winslow Jones created the first hedge fund. The exact timing of this first hedge fund is debatable since Jones created the fund in 1949, but only after altering the fund in 1952 did it have the three typical characteristics of a hedge fund – short selling, performance-based compensation, and leverage whose risk was shared through a partnership. The structure included long and short sales that gave rise to the name “hedge fund” because the fund “hedged” positions to minimize risk.

Though other hedge funds began emerging shortly after, it took almost 15 years before hedge funds became mainstream investment options. In the 1960s, hedge funds outperformed most mutual funds, but this outperformance happened quietly, and hedge funds remained a relatively unknown investment vehicle. This changed when Fortune published a piece highlighting how hedge funds had outperformed most mutual funds. Thanks in large part to this piece, by the late 1960s, hedge funds had become quite popular.

As their popularity grew, so did the amount of risk they took on. At the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s, the high levels of risk began leading to considerable losses. The bear market that started in 1973 exasperated the problem and forced many hedge funds to close. Hedge funds remained a less popular investment option until another article brought them back into the spotlight again.

In 1986, Institutional Investor published a piece highlighting the performance of Julian Robertson’s Tiger Fund. Again, the public became enamored with hedge funds. Again, higher risk funds became popular, and the additional risk led to massive losses and the closing of many hedge funds in the late 1990s and early 2000s. However, hedge funds did not fade into the background after their losses. On the contrary, even after the closure of many prominent hedge funds, the industry continued to grow.

The exact amount of assets in hedge funds is difficult to calculate. Still, the Office of Financial Research report estimates that net assets under management had reached $5.2 trillion as of the end of 2016.

Who Can Invest in a Hedge Fund?

With so much money invested in hedge funds, you may be wondering how you can start investing in them, but you may not be able to unless you meet specific requirements. As we saw looking at how hedge funds differ from mutual funds, hedge funds are not open to all investors in the same way other funds, such as mutual funds and ETFs, are. The two groups the SEC has said may invest in hedge funds are accredited, investors and institutional investors.

What exactly are these two types of investors, and why does the SEC deem them more capable of handling the risks associated with hedge funds?

The first type of investor who may invest in a hedge fund is an accredited investor. There are a few different ways to qualify as an accredited investor. Still, in general, an accredited investor is deemed wealthy enough to handle the risky nature of particular investments. For example, one way to qualify involves having a net worth of over $1 million.

The second type of investor is an institutional investor. Institutional investors are big organizations that invest large sums of money. Examples include banks, finance companies, labor union funds, and pension funds. Institutional investors are allowed to invest in hedge funds because it is assumed that they can protect themselves based on their size and knowledge.

Investment Options for Hedge Funds

We’ve mentioned several times now that hedge funds can include higher-risk investments, but what exactly do these higher-risk investments consist of?

This question is a bit complicated because, from a regulatory standpoint, the investment universe of a hedge fund is virtually unlimited, which means hedge funds can invest in anything they want. While hedge funds may invest in anything they like, each hedge fund has some limitations based on its investment mandate, a document every fund must have that creates parameters and guidelines for that fund’s investments. Investment options for a hedge fund include currencies, derivatives, real estate, land, etc. Hedge funds may also invest in more typical investments, such as stocks. This wide range of investment options makes a hedge fund different from other, more limited investment vehicles such as mutual funds.

This wide range of investment options may allow more flexibility, creating more opportunities for high returns, but it may also come with higher risk. Anyone considering investing in a hedge fund should take the time to become familiar with the types of investments included in the fund’s portfolio and the level of risk these investments come with. A hedge fund’s portfolio could theoretically look almost exactly like a mutual fund and have a similar risk, though this is rarely the case.

Hedge Funds and Fees

Another impact of less regulation on the unique compensation method used by hedge funds. The rest of the investing industry norm is to charge a percentage fee, around 1%, of the assets under management (AUM). While an investor may have additional costs, such as transaction fees or custodian fees, this percentage of AUM is the primary fee generally.

In contrast, hedge funds charge fees in a way commonly referred to as the “2 and 20” pay structure. In this payment method, the hedge fund manager receives two percent of assets under management and twenty percent of the annual profits. This fee structure has many implications for how a fund manager may handle the investments, and the structure has plenty of proponents and opponents.

The first thing to consider is the performance fee. Performance fees have become relatively rare in many areas of finance. In theory, performance fees incentivize managers to have higher performance. On the one hand, this seems like a logical argument – if the manager makes more if the fund performs well, it makes sense that the manager would work as hard as possible to make sure the fund does well.

The concern around performance fees, and why they’re not allowed in many other areas, is that the manager is incentivized to have a high-performing year but does not lose money if the fund performs poorly (unless managers have their own money invested in the fund). This could lead the fund manager to take on incredibly risky investments since if the risk pays off, the fund manager could make a lot of money but loses nothing if the risk negatively impacts performance.

While performance fees can be controversial, the two percent fee is an even more controversial aspect of the 2 and 20 pay structure. In theory, a manager could do nothing and still earn two percent of the fund’s AUM. While two percent may not sound like a lot, since only accredited and institutional investors may invest in hedge funds, many hedge funds are pretty significant; well into the billions of dollars, and fund managers, therefore, stand to make a lot of money. Even a relatively small hedge fund of 500 million allows a fund manager to earn 10 million a year, and that’s before including the 20% of any profit received.

The two percent part of the payment structure could further incentivize the fund manager to take on additional risk. If the fund manager invests in a high-risk investment that doesn’t work out and leads to negative performance for the fund, the manager still makes two percent.

Some protections help limit a manager’s ability to profit off the same money twice or take on excessive risk. Still, in general, the limited regulation of hedge funds allows for considerably more flexibility when it comes to compensation. This payment structure may help incentive fund managers. Still, it may also lead to increased risk for the investor, whether by limiting the manager’s incentive to perform well or overly incentivizing the manager to perform well and take on an unacceptable level of risk.

Leverage and Hedge Funds

Another aspect of hedge funds that increases the potential for both returns and risk that we have not yet looked at is how hedge funds use leverage.

Essentially, leverage is the act of borrowing money to increase potential returns. The concern is that it can also lead to more significant losses. An excellent way to think about leverage is trading on credit. Hedge funds can leverage a broker’s money and make a more substantial investment than they otherwise would have been able to make. Brokers charge interest to use this money, though, which means the return on leveraged investments must be worth the interest charged on the leverage.

Why do hedge funds use leverage?

While all investing is to make money, investors in hedge funds expect returns that far outpace the market. Leverage is one tool hedge fund managers use to make this happen. While leverage comes with no guarantee of higher returns, it provides yet another level of flexibility, much like the vast investment universe, which fund managers can use to increase how much they can invest (and therefore increase how much they earn in returns).

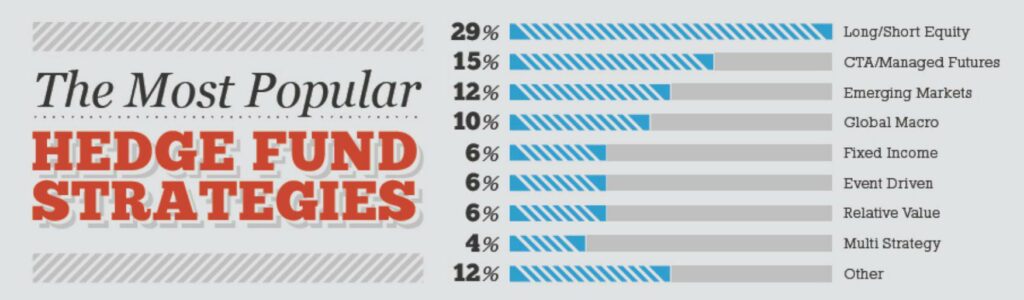

Most Common Hedge Fund Strategies

We’ve seen that hedge funds have almost unlimited investment options and strategies, but that doesn’t mean that there aren’t some more popular options than others. We’ll briefly look at seven of the most popular types of hedge funds and the strategies and investments they typically include.

Long/Short Equity

This is the original hedge fund model and is the strategy Alfred Winslow Jones used for the first hedge fund. As the name implies, this strategy attempts to take both upside (long) and downside (short) of price movements. This is done by taking long positions in stocks that are believed to be undervalued, earning money when the stock does well. At the same time, money is invested in shorting stocks (betting that the price will go down) of stocks believed to be overvalued to earn money when the price of these stocks drops.

Compared to other hedge funds with far more varied investments, the long/short equity strategy is comparatively straightforward.

Equity Market Neutral

Equity market neutral is similar to long/short equity in that it invests in equity and uses both long and short positions. The difference is that while long/short can favor a market direction such as 100% long and 30% short, and a market-neutral strategy does just that — attempts to remove the market from the returns.

An equity market-neutral strategy’s performance is measured by the spread between the fund’s long and short exposure.

Merger Arbitrage

Merger arbitrage is also known as risk arbitrage or risk arb. This hedge fund strategy involves purchasing and selling the stock of two merging companies simultaneously. You’ll often see the term “riskless” profits used to describe this strategy, but this does not mean that there is no risk involved since all investment involves risk.

The most significant risk with this strategy is if a deal does not go through. The benefit to this risk is that the stock of the merging companies typically sells at less than the acquisition price since there is the risk of the sale not occurring. This is why a crucial part of this strategy involves calculating whether a merger will happen or not and if it will happen when it closes. This review is conducted by someone called a merger arbitrageur.

Volatility Arbitrage

Unlike the previous strategies we’ve looked at, volatility arbitrage does not typically invest directly in stocks but instead typically invests in options or other derivative contracts. To understand how this strategy works, it’s essential to understand how volatility impacts derivative contracts.

The volatility of that asset impacts the volatility of the underlying asset of an option. Sometimes the forecasted volatility and the implied volatility are not the same. When this is the case, volatility arbitrage seeks to take advantage of these differences and profit.

Implementation of this strategy may occur in various ways, each with its advantages and disadvantages. No matter the implementation method, though, the volatility arbitrage strategy requires being right about two things – that implied volatility truly is under or overpriced and the timing of the strategy. Since both must be accurate for a profit to occur, these are also areas of potential risk for this strategy.

Convertible Bond Arbitrage

The underlying asset in the convertible bond arbitrage strategy is, not surprisingly, a convertible bond. Therefore, to understand this strategy, it’s necessary to know how convertible bonds work.

A convertible bond is not a typical bond. It is a mixture of a bond and a stock. A convertible bond is a form of short-term debt that can be converted into a company’s common shares. Convertible bond arbitrage involves taking both long and short positions on a convertible bond and the company’s stock that issued the convertible bond. This strategy aims to have the right amount of hedging between long and short positions to profit from market movements.

Distressed Hedge Funds

While not technically a strategy in the same way as previously mentioned types of hedge funds, this is a common type of hedge fund that you’ll likely hear about if you spend much time around hedge funds.

Distressed hedge funds are not in any trouble, and the “distressed” moniker has nothing to do with the quality of the hedge fund or the risk level of the assets it invests in. They are called distressed because these hedge funds typically invest in companies that are in the process of restructuring or in need of loan payouts. For example, a hedge fund may purchase bonds from a company going through a period of financial instability or if they think the company’s bonds may soon appreciate. While distressed hedge funds are not themselves distressed, this strategy does come with the risk that the purchased assets may fail to appreciate as anticipated.

Global Macro

The final strategy we’ll look at is called global macro. The assets this type of fund may invest in varies dramatically and may include many different types. This strategy attempts to pick investments based on the macroeconomic principles of various countries. This strategy may also include both long and short positions in many types of assets, including currency, commodities, futures, and equity and fixed income.

While we’ve now looked at a few of the most popular hedge fund strategies, it’s important to note that hedge funds are by no means limited to these types of strategies. As we’ve seen, the potential universe of hedge fund investments is quite large, which means a wide variety of different approaches may be implemented using different types of assets.

Regulating Hedge Funds

By now, we’re well aware that hedge funds are less regulated than many other investment vehicles, and we’ve seen how this impacts the management of hedge funds. But just because hedge funds are less regulated does not mean there’s no regulation. The current level of regulation may also increase as the already massive hedge fund industry continues to grow more significantly and more instances of insider trading and other breaches are reported.

At least in one respect, regulation of hedge funds has already begun to increase. Until the Dodd-Frank Act was enacted in 2010, hedge funds were not required to register, though the SEC had attempted to mandate registration in several previous instances. After the Dodd-Frank Act, hedge funds were required to register with the SEC.

Hedge Fund Infographic

The following infographic sums up the information we’ve discussed and provides other interesting statistics.